Each week, the Voice From the Crowd collection seeks to honour the story of a Canadian leader whose faith can be seen as an inextricable part of their contribution to Canada. Initially launched as the Thread of 1000 Stories initiative to mark Canada’s Sesquicentennial anniversary, this collection continues to grow and expand in partnership with senior editorial advisor, Lloyd Mackey, Founding Editor of the Online Encyclopedia of Canadian Christian Leaders. Join us as we continue to honour Canada’s faithful leaders past and present.

BY Preston jones

Lionel-Adolphe Groulx did not only write history, he made it, stoking the flame of Quebec nationalism. Groulx was a historian who believed that pride in the past would give French Canadians confidence in their future. Despite thirty-four years as a professor at the University of Montreal, Groulx was no ivory-tower academic. He engaged in popular journalism, wrote novels, advocated schemes designed to increase Quebec’s economic independence and initiated a Catholic students’ organization in the province.

“The essence of our being can be expressed in two words, French and Catholic.”

Groulx was born in Vaudreuil, Quebec, to a habitant family. His academic commitment was evident early in life. In 1898, he was awarded the Médaille Chapleau, which distinguished him as the best student of French, Latin, Greek, English, and modern history at the Séminaire de Sainte-Thérese-de-Blainville. The following year, Groulx was awarded the Governor-General’s Medal, again in recognition of his academic excellence. From 1918 to 1952, Groulx served as a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. Prizes, honourary doctorates, and similar awards continued to be conferred on Groulx to the end of his life.

Abbé Groulx – as he became generally known – attended seminary in Montreal and was ordained as a priest in 1903. Groulx never became a parish priest: he taught at the College de Vallefield in his home province; he studied in Rome, Fribourg, and Montreal; and in 1915, he became a professor of Canadian history at the University of Montreal. In his lifetime, Groulx wrote some thirty books, over twenty pamphlets and hundreds of newspaper and journal articles. From 1920 to 1928, he edited the nationalist review L’Action francaise. He founded the Institut d’histoire de l’Amérique francaise in 1946 and launched its academic publication, Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique francaise, the following year. Groulx never failed to speak and write his mind, for which he earned a reputation for controversy. In the mid-1930s, for instance, he publicly assailed Henri Bourassa, who had warned Groulx against excessive nationalism and racial pride. Bourassa’s Canadianism, Groulx said, was a thing of the past. Groulx’s heart and mind were with Quebec.

A major reason for Groulx’s combativeness and fervent nationalism was that he came of age in a period of crisis in Canadian French-English relations. In 1890, separate French language schools were abolished in Manitoba, even as the memory of the hanged Louis Riel, whom many French Canadians considered a martyr, was still sharp. The conscription crisis during the First World War further revealed the chasm separating French- and English-speaking Canadians. From his youth, Groulx was a committed French-Canadian nationalist, and although he did not advocate outright secession from Canada he did entertain separatism as a political possibility.

What mattered most to Groulx was that Quebec should preserve its French language, its French culture, and its Roman Catholic faith. Like most French-Canadian clerics, he regretted the French Revolution, French anticlericalism, and modern French unbelief. But he consistently maintained that the French people were a chosen race. In his view, the French Canadians were the heirs of a special divine mission. “The little [French-speaking] Canadian people of 1760 possessed all the elements of nationhood,” Groulx wrote in his La Naissance d’une race (The Birth of a People), published in 1919. “It had a land of its own, it had ethnic unity; linguistic unity, it had a history and traditions. But above all it had religious unity, the unity of the true faith.” The French Quebecer’s task, he consistently maintained, was to preserve in North America the French, Catholic, and agricultural way of life that had been threatened by the British conquest in 1759.

Groulx’s political pilgrimage extended along the verges of the ultra-right. Not content with supporting Charles Maurras in the 1920s, in the following decade he at times praised figures like Mussolini, Salazar and Dollfuss. But in spite of this ultra-conservative orientation, Groulx’s major historical works proved an inspiration to Quebec nationalists of all complexions, conservative or socialist, separatist or merely autonomist. Groulx enshrined his vision for Quebec nationalism in his massive Histoire du Canada francais dupuis la Découverte (The History of French Canada Since Discovery), which appeared in several volumes between 1950 and 1952. That vision was given practical manifestation when combined with the political talents of men like Rene Levesque. Groulx maintained that if a Catholic, French-speaking community could be safely preserved within Confederation, then Quebec should stay in Confederation. But if Confederation imperilled French-Canadian culture, then Quebec should go its own way. Whatever the case, Quebec came first. Yet Groulx did not believe that Quebecers should only turn inward. Indeed, their faith obligated them to be a witness to the world. In 1953, Groulx declared that he loved French Quebec for “the ties of blood and history” that bonded him to it, but that he loved it primarily because of the thousands of Catholic missionaries that it had sent all over the globe. If nothing else saved Quebec from being eventually set aside by Providence, the work of its missionaries would. “It’s because of them that I hope,” Groulx wrote.

Although Groulx’s staunch nationalism paved the way for Quebécois separatism, he did not approve of the secularism that he saw prevailing in Quebec, particularly after l960. Against secularist nationalists, Groulx argued that Quebecers should not speak of their French language as if it could be separated from their Catholic faith. “In place of speaking of language and faith, I prefer to speak of the soul and faith,” he had written earlier, in 1935.

In a 1949 speech delivered in Ottawa, he summarized: “The essence of our being can be expressed in two words, French and Catholic. French and Catholic we have been, not merely since our arrival in America, but for the past thousand years.” Groulx believed that it was God’s will for French civilization to survive in North America. For if it was true to its task, he wrote, “a small people united by the true faith” could surely radiate “the living splendour of a Christian civilization.”

In his final years, Groulx saw the gradual rejection of many of his earlier ideas, and he knew that his legacy would be debated after his death. In his last will and testament, he wrote, “I think it will not be difficult to make sense of everything I said, wrote, or did, or even to understand the passion with which I did it.” Nonetheless, his views on race have been a source of debate for decades, as has his anti-Semitism. What is clear, however, is that he loved Quebec, its people, and its traditional Catholic faith. Groulx never ceased to be, in attitude, completely a priest and in feeling completely a peasant. “In view of these motives and this inspiration for my actions,” he wrote just before his death in 1967, “may God forgive me and grant me mercy.”

FURTHER READING

- Groulx, Lionel. Mes Mémoires, 4 vols. Montreal: Fides, 1974.

- Lacroix, ed. Lionel Groulx. Montreal: Fides, 1967.

- Trofimenkoff, Susan Mann. Abbé Groulx: Variations on a Nationalist Theme. Toronto: Clark Copp Publishing, 1973.

-

Dr. Preston Jones is a professor of history at John Brown University in Siloam Springs, Arkansas. He received his PhD at the University of Ottawa in 1999. His dissertation explored the relationship of the Bible to Canadian Culture in the late 19 th century. He has received several awards, including a Fulbright Scholarship for study in Canada and a fellowship with the Pew Program in Religion and American History. He served in the U.S. Navy from 1986 to 1990. Because of his interest in seeing the U.S. military end its involvement with the Southeast Asian brothel industry, he served on the advisory board of ECPAT-USA, an international organization devoted to combating child prostitution. Dr. Jones has run 22 marathons.

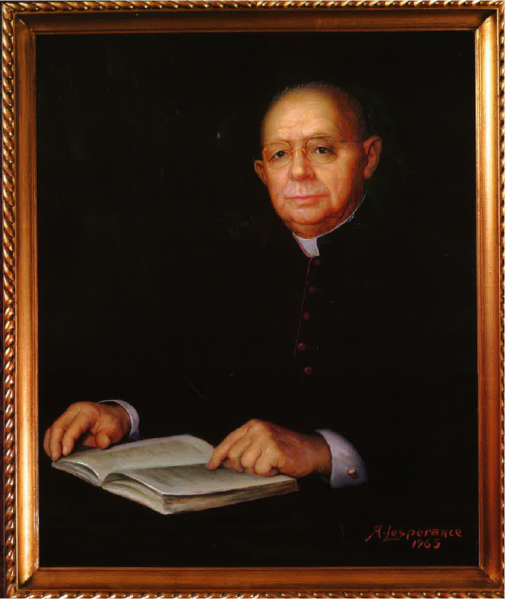

This portrait is drawn, by permission, from Canada: Portraits of Faith (C:POF). C:POF is a popular coffee table book published in 1996 and edited by Michael D. Clarke.

Image copyright © 1998 by Michael D. Clarke, used with permission.